Sherry Turkle, a professor of science, technology and society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and author of the book “Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology and Less From Each Other,” did a series of studies with Paro, a therapeutic robot that looks like a baby harp seal and is meant to have a calming effect on patients with dementia, Alzheimer’s and in health care facilities. The professor said she was troubled when she saw a 76-year-old woman share stories about her life with the robot.

“I felt like this isn’t amazing; this is sad. We have been reduced to spectators of a conversation that has no meaning,” she said. “Giving old people robots to talk to is a dystopian view that is being classified as utopian.” Professor Turkle said robots did not have a capacity to listen or understand something personal, and tricking patients to think they can is unethical.

[…]

“We are social beings, and we do develop social types of relationships with lots of things,” she said. “Think about the GPS in your car, you talk to it and it talks to you.” Dr. Rogers noted that people developed connections with their Roomba, the vacuum robot, by giving the machines names and buying costumes for them. “This isn’t a bad thing, it’s just what we do,” she said.

[…]

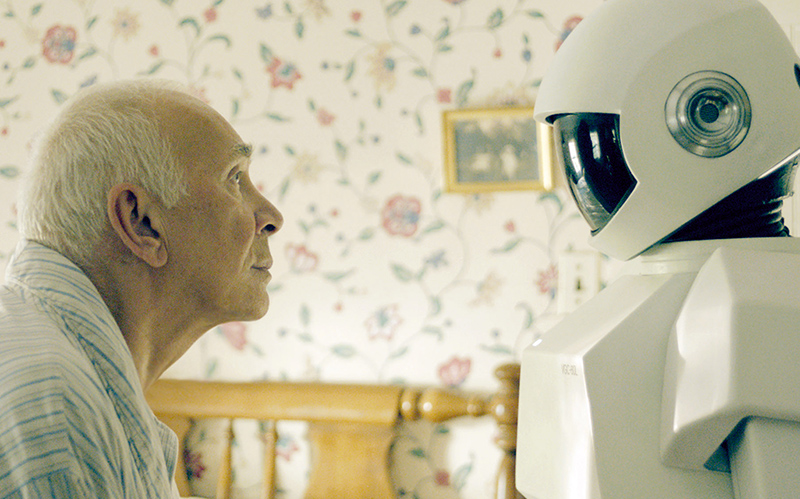

As the actor Frank Langella, who plays Frank in the movie, told NPR last year: “Every one of us is going to go through aging and all sorts of processes, many people suffering from dementia,” he said. “And if you put a machine in there to help, the notion of making it about love and buddy-ness and warmth is kind of scary in a way, because that’s what you should be doing with other human beings.”

Ref: Disruptions: Helper Robots Are Steered, Tentatively, to Care for the Aging – The New York Times