Ref: via algopop

Ref: via algopop

Today, anyone with a laptop can run commercial chess software that will reliably defeat all but a few hundred humans on the planet. Isn’t the spectacle of puny humans playing error-strewn chess games just a nostalgic throwback?

Such a dismissive attitude would be in tune with the spirit of the times. Our age elevates the precision-tooled power of the algorithm over flawed human judgment. From web search to marketing and stock-trading, and even education and policing, the power of computers that crunch data according to complex sets of if-then rules is promised to make our lives better in every way. Automated retailers will tell you which book you want to read next; dating websites will compute your perfect life-partner; self-driving cars will reduce accidents; crime will be predicted and prevented algorithmically. If only we minimise the input of messy human minds, we can all have better decisions made for us. So runs the hard sell of our current algorithm fetish.

[…]

More recently, Gary Marcus, professor of psychology at New York University, offered a vivid thought experiment in The New Yorker. Suppose you are in a self-driving car going across a narrow bridge, and a school bus full of children hurtles out of control towards you. There is no room for the vehicles to pass each other. Should the self-driving car take the decision to drive off the bridge and kill you in order to save the children?

What Marcus’s example demonstrates is the fact that driving a car is not simply a technical operation, of the sort that machines can do more efficiently. It is also a moral operation. (His example is effectively a kind of ‘trolley problem’, of the sort that has lately been fashionable in moral philosophy.) If we let cars do the driving, we are outsourcing not only our motor control but also our moral judgment.

[…]

If self-driving cars and speech-policing systems are going to make hard moral decisions for us, we have a serious stake in knowing exactly how they are programmed to do it. We are unlikely to be content simply to trust Google, or any other company, not to code any evil into its algorithms. For this reason, Morozov and other thinkers say that we need to create a class of ‘algorithmic auditors’ — trusted representatives of the public who can peer into the code to see what kinds of implicit political and ethical judgments are buried there, and report their findings back to us. This is a good idea, though it poses practical problems about how companies can retain the commercial edge provided by their computerised secret sauce if they have to open up their algorithms to quasi-official scrutiny.

[…]

If you are feeling gloomy about the automation of higher education, the death of newspapers, and global warming, you might want to talk to someone — and there’s an algorithm for that, too. A new wave of smartphone apps with eccentric titular orthography (iStress, myinstantCOACH, MoodKit, BreakkUp) promise a psychotherapist in your pocket. Thus far they are not very intelligent, and require the user to do most of the work — though this second drawback could be said of many human counsellors too. Such apps hark back to one of the legendary milestones of ‘artificial intelligence’, the 1960s computer program called ELIZA. That system featured a mode in which it emulated Rogerian psychotherapy, responding to the user’s typed conversation with requests for amplification (‘Why do you say that?’) and picking up — with its ‘natural-language processing’ skills — on certain key words from the input. Rudimentary as it is, ELIZA can still seem spookily human. Its modern smartphone successors might be diverting, but this field presents an interesting challenge in the sense that, the more sophisticated it gets, the more potential for harm there will be. One day, the makers of an algorithm-driven psychotherapy app could be sued by the survivors of someone to whom it gave the worst possible advice.

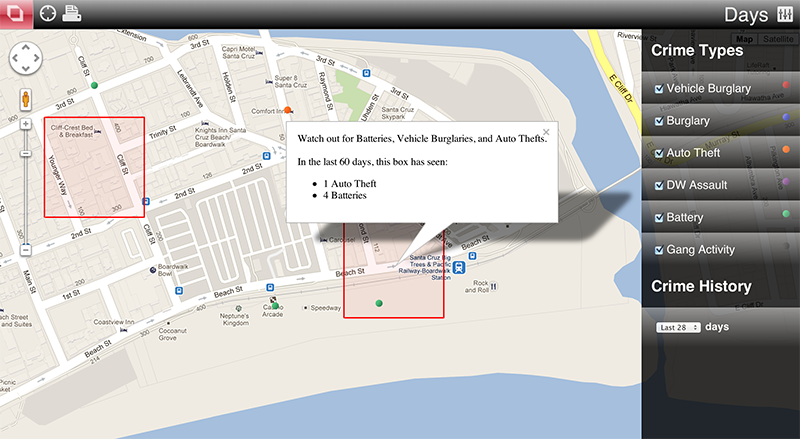

The federally-funded cloud-based crime prediction software known as PREDPOL, uses mathematical algorithms similar to ones used in earthquake prediction to predict when and where a future crime is most likely to take place down to a 500-square foot area. The program combines five years’ worth of past crime data with sociological information about criminal behavior.

Ref: Seattle Police Deploy Crime Prediction Software City-Wide – SecretsOfTheFed