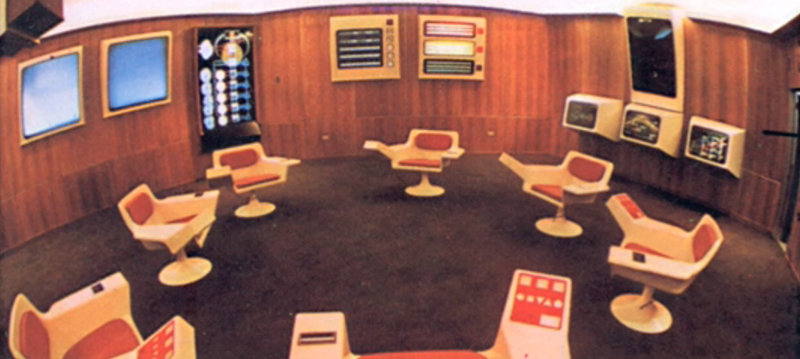

That was a challenge: the Chilean government was running low on cash and supplies; the United States, dismayed by Allende’s nationalization campaign, was doing its best to cut Chile off. And so a certain amount of improvisation was necessary. Four screens could show hundreds of pictures and figures at the touch of a button, delivering historical and statistical information about production—the Datafeed—but the screen displays had to be drawn (and redrawn) by hand, a job performed by four young female graphic designers. […] In addition to the Datafeed, there was a screen that simulated the future state of the Chilean economy under various conditions. Before you set prices, established production quotas, or shifted petroleum allocations, you could see how your decision would play out.

One wall was reserved for Project Cyberfolk, an ambitious effort to track the real-time happiness of the entire Chilean nation in response to decisions made in the op room. Beer built a device that would enable the country’s citizens, from their living rooms, to move a pointer on a voltmeter-like dial that indicated moods ranging from extreme unhappiness to complete bliss. The plan was to connect these devices to a network—it would ride on the existing TV networks—so that the total national happiness at any moment in time could be determined. The algedonic meter, as the device was called (from the Greekalgos, “pain,” and hedone, “pleasure”), would measure only raw pleasure-or-pain reactions to show whether government policies were working.

[…]

“The on-line control computer ought to be sensorily coupled to events in real time,” Beer argued in a 1964 lecture that presaged the arrival of smart, net-connected devices—the so-called Internet of Things. Given early notice, the workers could probably solve most of their own problems. Everyone would gain from computers: workers would enjoy more autonomy while managers would find the time for long-term planning. For Allende, this was good socialism. For Beer, this was good cybernetics.

[…]

Suppose that the state planners wanted the plant to expand its cooking capacity by twenty per cent. The modelling would determine whether the target was plausible. Say the existing boiler was used at ninety per cent of capacity, and increasing the amount of canned fruit would mean exceeding that capacity by fifty per cent. With these figures, you could generate a statistical profile for the boiler you’d need. Unrealistic production goals, overused resources, and unwise investment decisions could be dealt with quickly. “It is perfectly possible . . . to capture data at source in real time, and to process them instantly,” Beer later noted. “But we do not have the machinery for such instant data capture, nor do we have the sophisticated computer programs that would know what to do with such a plethora of information if we had it.”

Today, sensor-equipped boilers and tin cans report their data automatically, and in real time. And, just as Beer thought, data about our past behaviors can yield useful predictions. Amazon recently obtained a patent for “anticipatory shipping”—a technology for shipping products before orders have even been placed. Walmart has long known that sales of strawberry Pop-Tarts tend to skyrocket before hurricanes; in the spirit of computer-aided homeostasis, the company knows that it’s better to restock its shelves than to ask why.

[…]

Flowers suggests that real-time data analysis is allowing city agencies to operate in a cybernetic manner. Consider the allocation of building inspectors in a city like New York. If the city authorities know which buildings have caught fire in the past and if they have a deep profile for each such building—if, for example, they know that such buildings usually feature illegal conversions, and their owners are behind on paying property taxes or have a history of mortgage foreclosures—they can predict which buildings are likely to catch fire in the future and decide where inspectors should go first.

[…]

The aim is to replace rigid rules issued by out-of-touch politicians with fluid and personalized feedback loops generated by gadget-wielding customers. Reputation becomes the new regulation: why pass laws banning taxi-drivers from dumping sandwich wrappers on the back seat if the market can quickly punish such behavior with a one-star rating? It’s a far cry from Beer’s socialist utopia, but it relies on the same cybernetic principle: collect as much relevant data from as many sources as possible, analyze them in real time, and make an optimal decision based on the current circumstances rather than on some idealized projection.

[…]

It’s suggestive that Nest—the much admired smart thermostat, which senses whether you’re home and lets you adjust temperatures remotely—now belongs to Google, not Apple. Created by engineers who once worked on the iPod, it has a slick design, but most of its functionality (like its ability to learn and adjust to your favorite temperature by observing your behavior) comes from analyzing data, Google’s bread and butter. The proliferation of sensors with Internet connectivity provides a homeostatic solution to countless predicaments. Google Now, the popular smartphone app, can perpetually monitor us and (like Big Mother, rather than like Big Brother) nudge us to do the right thing—exercise, say, or take the umbrella.

Companies like Uber, meanwhile, insure that the market reaches a homeostatic equilibrium by monitoring supply and demand for transportation. Google recently acquired the manufacturer of a high-tech spoon—the rare gadget that is both smart and useful—to compensate for the purpose tremors that captivated Norbert Wiener. (There is also a smart fork that vibrates when you are eating too fast; “smart” is no guarantee against “dumb.”) The ubiquity of sensors in our cities can shift behavior: a new smart parking system in Madrid charges different rates depending on the year and the make of the car, punishing drivers of old, pollution-prone models. Helsinki’s transportation board has released an Uber-like app, which, instead of dispatching an individual car, coördinates multiple requests for nearby destinations, pools passengers, and allows them to share a much cheaper ride on a minibus.

[…]

For all its utopianism and scientism, its algedonic meters and hand-drawn graphs, Project Cybersyn got some aspects of its politics right: it started with the needs of the citizens and went from there. The problem with today’s digital utopianism is that it typically starts with a PowerPoint slide in a venture capitalist’s pitch deck. As citizens in an era of Datafeed, we still haven’t figured out how to manage our way to happiness. But there’s a lot of money to be made in selling us the dials.